Quagga Mussels

Identification

Quagga mussels are small bivalves that exhibit several different morphs, and can be black, white, brown, or cream-colored. They usually have dark and light bands similar to zebra mussels, but some morphs have no distinct stripes. They can be differentiated from zebra mussels (another exotic invader not yet found in Vermont) by placing a specimen on a flat surface. Zebra mussels are stable on their flattened underside while quagga mussels will fall over, as they lack a flat underside. Also, zebra mussels are typically more angular in shape, whereas quagga mussels exhibit more of a "D" shape.

Dreissenid mussels (which includes zebra and quagga mussels) are generally small, and rarely exceed 5 cm in length. Dreissenid mussels are the only genus of freshwater mussels that utilize byssal threads, which allows them to attach to objects, which may include rocks, aquatic plants, dock pilings, other shellfish, and any other hard or semi-hard underwater surface. If you encounter small shellfish attached to any surface in a freshwater system, then you've found zebra or quagga mussels.

Biology

Origin

Both zebra and quagga mussels are native to the Black and Caspian Seas of Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

Habitat

Dreissenid mussels attach to any stable substrate in the water column or on the bottom, which can include natural and artificial surfaces and native crustaceans and bivalves. The optimal temperature range for both species appears to be between 17-25 degrees C, but they are able to survive in a wide range of temperatures, from 3-30 degrees C. While unable to persist in completely anoxic conditions, they can survive in low oxygen conditions for short periods of time. Both zebra and quagga mussels can also tolerate low levels of salinity, but are unable to survive in saltwater environments.

LifeCycle

Dreissenid mussels are dioecious, with fertilization occuring in the water column. When water temperatures are suitable (roughly 14-16 degrees C), females release eggs into the water column, which are fertilized by sperm released by males. After fertilization, the larvae (veligers) are free-swimming for up to a month. During this time, veligers are carried through currents and other natural movements of water. Since they are free-floating in the water at this stage, they can be easily transported to novel waterbodies in small amounts of water. Their juvenile stage begins when larvae settle to the substrate and use a "foot" for movement until a suitable surface is found. They then attach themselves using an anchor-like substance called byssal threads, where they typically stay throughout their lifetime.

Vermont Distribution

To date, no quagga mussels have been documented in Vermont waters.

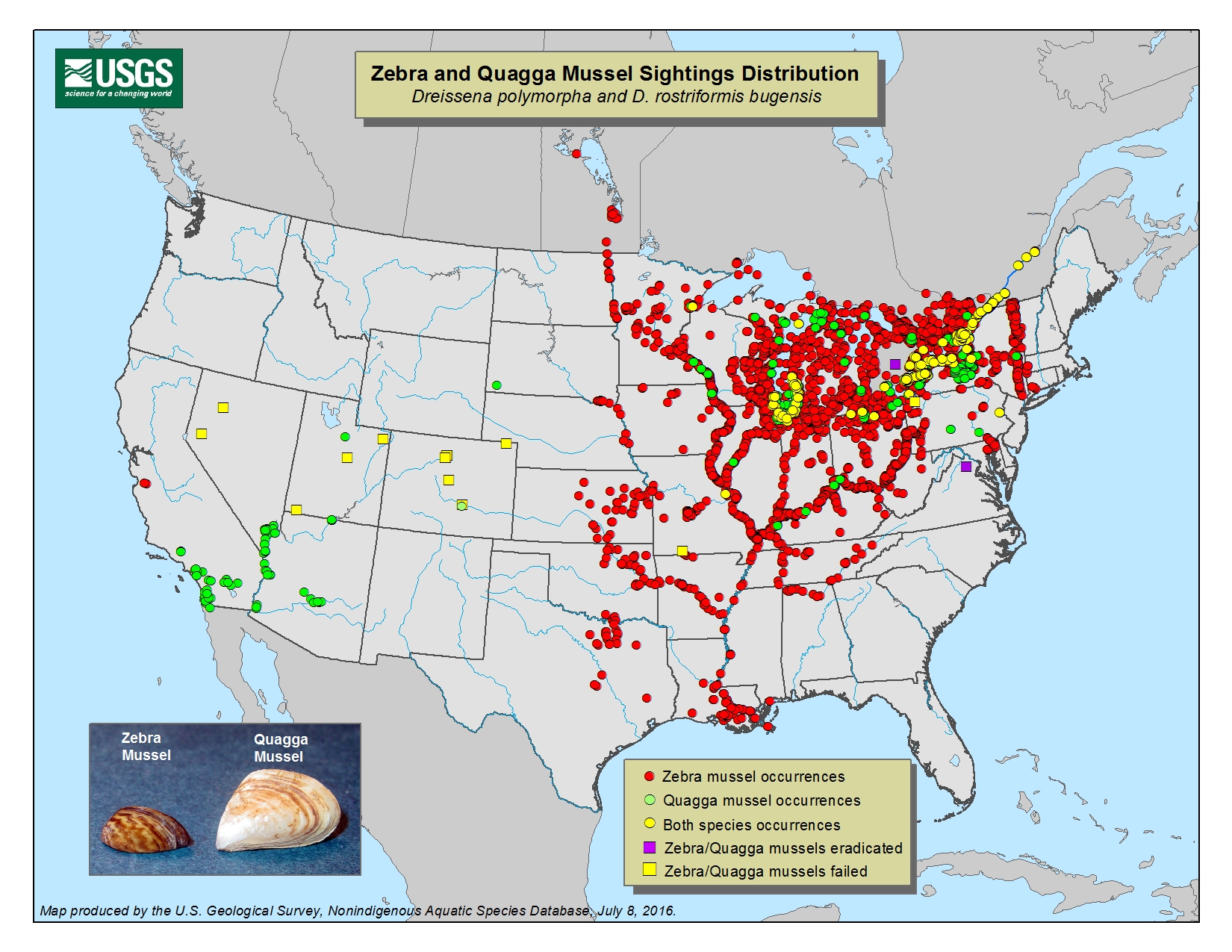

Dreissenid mussels are now found through much of the U.S.

How You Can Help

For most aquatic invasive species, humans are the primary vector of transport from one waterbody to another. Many of these nuisance plants and animals can be unknowingly carried on fishing gear, boating equipment, or in very small amounts of water in a watercraft. The easiest and most effective means to ensure that you are not moving aquatic invasives is to make sure that your vessel, as well as all your gear, is drained, clean, and dry.

BEFORE MOVING BOATS BETWEEN WATERBODIES:

-

CLEAN off any mud, plants, and animals from boat, trailer, motor and other equipment. Discard removed material in a trash receptacle or on high, dry ground where there is no danger of them washing into any water body.

-

DRAIN all water from boat, boat engine, and other equipment away from the water.

-

DRY anything that comes into contact with the water. Drying boat, trailer, and equipment in the sun for at least five days is recommended. If this is not possible, then rinse your boat, trailer parts, and other equipment with hot, high-pressure water.

Interested in monitoring for aquatic invasives?

- Join the VIPs! Vermont Invasive Patrollers help search for new infestations so we can respond immediately and prevent them from becoming established.